Hey Folks,

Here’s a REAL snowshoe hare photo, taken on my recent sojourn to the northern side of Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. I was very surprised at how little sign of snowshoe hares there was in this area – negligible. Everywhere else, it seems, the woods are crawling with them. This is at, or close to, the peak of the cycle for snowshoe hares; a 10 year population fluctuation that seems to be pretty consistent.

Why is the Snowshoe Hare Population so volatile?

Sometimes the cycle might be 9 years, or 11, but it’s not usually far off. The population rises steadily, then faster, peaks, and falls drastically, almost completely, in a single year. Ecologists aren’t sure as to what causes the drop in numbers, though theories abound, as always.

One theory is simply over-population causes starvation, though there is evidence from a few studies that even with ample food sources, the hare populations still drop. Another is that the increase in hare numbers yields an equal increase in predator numbers, and the resulting high population of predators causes the hare numbers to drop.

Foxes, wolves, coyotes, owls, hawks, eagles, marten, weasels, etc all prey on snowshoe hares; even arctic ground squirrel and red squirrels kill and eat baby snowshoe hares (called Leverets, unless you’re a red squirrel, in which case they’re called ‘dinner’).

The Snowshoe Hare and Lynx Population Relationship

However, perhaps the best known of snowshoe hare predators is the Canadian Lynx.

The relationship between snowshoe hares and lynx populations is well known, and graphed in almost any ecology text. The lynx population tends to follow, with a year or 2 lag, behind that of the hare.

Note on the graph above

Between 1845 and 1935, the Hudson Bay Company kept meticulous records of the lynx and hare pelts they purchased from trappers across Canada. For ninety years, these counts have provided a rare window into the population dynamics of the North. While pelt numbers are an approximate measure, they serve as a reliable proxy for how these two species were actually performing in the wild.

The relationship between the Canada lynx and the snowshoe hare is a classic real-world example of a predator-prey system. Throughout most of their range, lynx rely almost exclusively on hares for food. In turn, hares are the primary target for the lynx. While actual ecosystems are rarely as tidy as a simplified model, the bond between these two is remarkably direct. Other predators and prey exist, but they play a limited role compared to the core cycle of these two species.

Right now, lynx numbers are pretty high, meaning it’s a good time to try photograph them. (I got one last winter, and my friend Ron got one this last fall – his photo is better than mine, but I got mine first! 🙂 )

Speaking of which, I did see a lynx this last trip, but the day was over, it was almost dark, and I wasn’t able to photograph him. Ironically, the lynx was traveling along a trail that had been laid in by a trapper, and only a week earlier the area was loaded with traps.

Anyway, no one’s quite sure what causes the snowshoe hare numbers to crash so dramatically.

One theory is that willows, their main food source, build up a toxin that the hares avoid, and after a number of years, the willows in the area get too toxic, and the hares won’t browse the willow, and so starve over the winter. This seems to be apparent in some places, but not in others.

What’s really cool, is that the willow toxins tend to be lower down on the plant, in the first foot or 2 above the snowline, and the higher parts of the willow, out of the snowshoe hare’s reach, aren’t toxic – they remain palatable to that other great willow browser, the moose.

Pretty cool. But again, there is evidence that this isn’t the reason, or certainly not the only reason, that the hare populations crash.

Another theory involving the predators is that they stress the hares enough to affect their ability to reproduce – the woods are really alive with with raptors, lynx, foxes, coyotes, etc, and they all chase the hares. But, nobody really seems to understand completely what goes on, which is perhaps as it should be.

One thing that makes it difficult to study is the length of the cycle; 10 years is a long time to study a single species, and in order to verify some recorded data, one has to wait 10 more years, which means few researchers know much about it, firsthand. One fellow in Canada, I believe, has studied them for 40 years, so he probably know more about them than anyone. I forget his name though.

The cycle seems to be pretty consistent all across the northern boreal forest, from eastern Canada to western Alaska.

After the hare population crashes, the lynx population tends to follow, within a year or 2. Then it takes about 3 years or so for the hare numbers to start increasing again.

This could be because of toxic willows, or it could be due the physiological changes from stress; i.e., it takes a few generations to breed this stress factor back out of the population.

Such is the way of the snowshoe hare and the lynx.

More Snowshoe hares

Here’s a look at a Snowshoe hare (lepus americanus) just as it starts to pelage and change to its summer coat, and below, a look at another hare further along in the process.

I like to try to photograph animals in the various stages of their phenology, and also to try some different kinds of compositions – the one below showing a little more of the forest this snowshoe hare lives in, and what they might do this time of year; sit in the morning sun and catch some rays after a long, cold winter.

Speaking from experience, I can assure you the sun feels mighty good as the days started to finally get longer.

One thing you’ll notice here, if you look closely, is the black tips of the ears. Even in the middle of winter, the snowshoe hare ears keep those little black tips, though I’ve never understood why; in some places further south, like Oregon and Washington, Snowshoe hares can stay the dark summer brown all year long. You also get a little more of a look at the size of those big back feet here.

Snowshoe hares have a pretty tough winter, and browse mostly on willow and birch. but also aspen and poplar bark, some spruce, and whatever other greenery they can find. Dwarf birch seems to be their favorite. It’s can be pretty impressive to see the forest after a winter of heavy browsing by an intensive snowshoe hare population, lots of small trees and shrubs stripped bare; you can see some of the browsed vegetation in the photo below, and the culprit at hand.

And a fun one about Snowshoe hares =/= No Shoes

When I finally figured out about these snowshoes, the next thing I heard about was these ‘snowshoe hairs’. I saw one in the woods, and was able to get a picture:

One of the coolest thing about these creatures is that they change their coats out with the season – very fashionable – darker for the warmer months, and a white coat for the colder, winter months. Pretty snazzy.

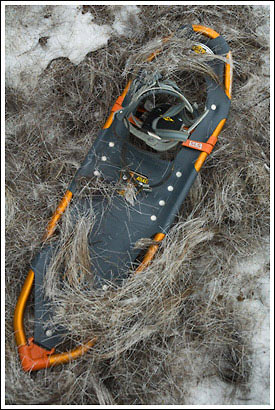

Another aspect is how large their feet are. Regular rabbits and hares have pretty large hind feet, but nothing like the snowshoe hair. You can see a comparison in the image below; snowshoe hair (winter molt) on the left, and a ‘regular rabbit’ on the right. Pretty stark, huh?

The snowshoe hair is perfectly equipped to traverse the deep soft snow of the northern winter. Lucky buggers!

Quick quiz; Who knows which animal has the greatest foot loading to body weight ratio for traversing over soft winter snow (it’s not the snowshoe hare)?

Cheers

Carl

Neat post Carl – always learning a thing or two when I visit here. I understand they make for some pretty good slippers for guys who get tired of going “no shoes” up there.

Hey Mark,

Thanks for dropping in. I’d thought of the slippers thing, too. Especially when it got really cold this winter. But I just went with extra wool socks instead. 🙂

Cheers

Carl