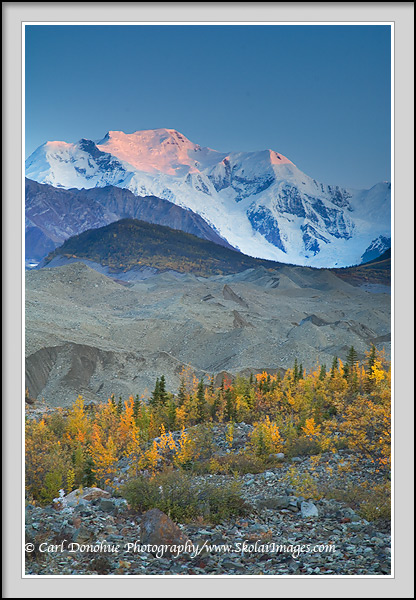

Mt. Blackburn stands tall to catch the sun’s first rays of alpenglow, high above the Kennicott Valley, early fall, Wrangell-St. Elias National Park, Alaska.

Hey Folks,

I just visited my friend Mark Graf’s great blog, and read with interest his commentary on mountains and the import and grandeur of nature, the role it can play in our lives. Mark prefaces his post with the legendary John Muir, so I’ll do the same:

“Walk away quietly in any direction and taste the freedom of the mountaineer. Camp out among the grasses and gentians of glacial meadows, in craggy garden nooks full of nature’s darlings. Climb the mountains and get their good tidings, Nature’s peace will flow into you as sunshine flows into trees. The winds will blow their own freshness into you and the storms their energy, while cares will drop off like autumn leaves. As age comes on, one source of enjoyment after another is closed, but nature’s sources never fail. – John Muir, Our National Parks, 1901”

While I think it’s a fantastic photo Mark posted, and a great post, (I’d ask that you read it and the comments that follow) I have to be the lone opponent in the discussion here;

I’ve long loved that quote of Muir’s (and countless others from him), but I think the phrase “Climb the mountains and get their good tidings” and the entire point of Muir’s commentary MUST run both ways; i.e., it also stands as “Climb the mountains and offer them your good tidings”. If this isn’t true, the entire point of the phrase is lost, IMO.

The mountains do, I believe, need our awareness and appreciation every bit as critically as we need their grandeur, as we need the Robin’s crystalline song, the wolf’s wild eyes and the great grizzly’s lordliness. It’s a 2-way relationship, or there is no relationship at all; if there’s no real relationship there, then our appreciation of the mountains is merely another form of narcissism, of it’s a self-centered hedonism, our ego sneaking in yet again, relentlessly, through the back door.

I once had this conversation years ago with a great friend, camped high on a mountain top in Wrangell-St. Elias National Park. As he swept his arms open to welcome the vast landscape before us, his comment that “all this benefits from our appreciation as much as we benefits from it’s beauty” rang profoundly clear – how could it not, I realized.

The “environmental movement” misses much of what it most desperately needs when it focuses exclusively on the singular benefit humans receive from the natural world. Indigenous cultures across the world, for example, have long held that the world they live within benefits from, enjoys and appreciates their humanness, just as they’ve benefitted from and enjoyed and appreciated the specialness of the creatures and features they live amongst. The words of Thoreau and Muir, the imagery of Jackson and Adams, the melodies of Bach and Mozart, etc, are a gift not to ourselves, but to (and from) existence itself. They DO mean something. So too does the beautiful photograph Mark posted, and the thoughts, words and most of all the care and respect that the folks in that discussion offer. That part of our humanness is our greatest gift to the world, and it’s as important as the mountain itself.

Don’t get me wrong, I understand the sentiment about our relative insignificance and the scale of a universe that is so beyond us. But it’s a paradox – we are simultaneously every bit as critical, as important and valuable as the trees, the salmon the canyons and the mountains. I’m reasonably sure the mountain would not “be rid of us altogether” though; I’ll wager it seeks our reconnection. The beauty of the relationship lies in the patience with which the mountain awaits our return – that, friends, is unconditional – which is why Muir wrote that “nature’s sources never fail”.

RIP, Mr Muir.

Cheers

Carl

Well, there you go, posting another mountain to make someone feel small and insignificant – in great light yet. 🙂

I know where you are coming from Carl. I wonder in that statement ““all this benefits from our appreciation as much as we benefit from it’s beauty” – is that benefit an acknowledgement that we as a species tend to be consumptive – and any appreciation leads to preservation?

As with the mountain, I had similar feelings when being “tolerated” by the bears. Ultimately I don’t know if my presence was of any benefit to them unless I was able to offer some protection of their habitat, their own existence, or perhaps give them some fresher fish heads to chew on. Maybe their day was enriched by seeing something different, giving them curiosity about something new in their environment. I am just not sure their life experience is any richer with me being around. I’d like to think that a mutual, respectful coexistence can offer that, but I remain skeptical.

Good thoughts as always – and killer image.

Beautiful image and thoughts. I was just posting on a somewhat tangential subject, how our photographic subjects are impacted by our presence. It is my hope that it is always in a positive manner either directly or indirectly (awareness leading to conservation), however I know that can’t always be true. I’m not sure how it applies to landscapes or mountains but I know the experiences in the backcountry provide the inspiration and motivation for so many aspects of our lives so there has to be some intrinsic value of both the landscape as well as that inspiration that is drawn from it. I was never all that good at this philosophical stuff but it has me thinking.

Great shot Carl, and interesting post!

Mark asked:

“I wonder in that statement ““all this benefits from our appreciation as much as we benefit from it’s beauty” – is that benefit an acknowledgement that we as a species tend to be consumptive – and any appreciation leads to preservation?”

Hey Mark,

No, I don’t think it’s an acknowledgement or expression of the negative at all. I think it’s an illustration of the Nature of Reciprocity, or, better yet, the Reciprocity of Nature. That said, it’s certainly clear that only through real appreciation and respect for these creatures and places will we take steps to refrain from destroying them.

Framing the discussion with the question “do the bears have a better day when you visit them” kinda misses part of the equation; it’s a narrow and somewhat anthropomorphic premise. Instead, consider it this way; in your post, Guy also discusses the relative infancy of, say, Denali; how do we explain the grandeur and significance of a mountain that is also simply a mere blip on the screen of time and space? Remove ourselves from the equation, and where lies the majesty of a mountain? What are the good tidings of a mountain without you or I to receive them? Does the mountain offer the soaring eagle its good tidings? If so, then does the eagle have a better day because of it? If the mountain does NOT offer those good tidings, does the eagle suffer?

These are not academic questions; I expect the mountain does offer it’s good tidings, to all, to the universe, and the universe receives and welcomes them. So too does the salmon, the blueberry, the eagle, the glacier and moose. So what are OUR good tidings? Surely we have more to offer than a promise to make an effort to refrain from destroying our fellow creatures and the world around us? That’s a relatively recent phenomena, the last few thousand years that we’ve caused so much hell – did we exist for a million years before that with nothing of our own to offer the world but our existence?

Ultimately, I think our greatest gift to the world is our awareness, our consciousness – and so often, that is illustrated through our art; not always, but remarkably frequently. What’s Denali’s good tiding to the world? What’s the gift of the grizzly, and does the Sockeye Salmon receive that same gift?

We live in this world in one state – and that state is relationship. Relationship, by construct, is mutual. I feel we HAVE to learn the value of our own good tidings if we’re to fully understand and nurture our relationship with the world.

Cheers

Carl

Hey Drew,

Thanks for the note and kind words.

Yes, we do impact wildlife, for sure, and landscape, in a very physical way – for sure. But I think that impact is ultimately secondary – if we pay attention to how we relate to the world, particularly as photographers, I think everything else follows.

Cheers

Carl

I suppose that is what makes me wonder – that “we have more to offer than a promise…” I’d like to think so, and I really am not trying to be negative. Perhaps humble is more appropriate? Is it the mountain that is enriched by me making art of it, or is it myself and other beings that might appreciate it? If the mountain is enriched by my art, then am I not anthropomorphizing it?

What you mention is exactly what I was trying to avoid – the anthropomorphic premise that in some way, there is some benefit to nature from our existence. The mountain doesn’t “need” majesty or admiration unless it is for the benefit of its own preservation. The one mountain’s significance to the universe is miniscule, which makes me even smaller. For that matter, this planet could be viewed in the same fashion.

I do see value in the relationships. It is for our benefit, and ultimately the mountain’s benefit because of our good tidings for it. I just don’t know how much the mountain’s existence would have changed, and its relationship to all of the other beings around it would have been, if we never walked out of the ocean. That is what I try to wrap my brain around … and obviously haven’t quite figured it out yet. 🙂

Hey Mark,

No – I don’t think that’s anthropomorphic at all. Can mountains be enriched? It’s probably very anthropocentric to say ‘no’.

You asked:

“I just don’t know how much the mountain’s existence would have changed, and its relationship to all of the other beings around it would have been, if we never walked out of the ocean. ”

Let’s put it another, simpler way; how do you benefit from the mountain’s good tidings? Why do you suggest a mountain, or a bear, can not benefit in exactly the same way from your own good wishes? How does your existence change because of the mountain? In a very physical sense, you’re not entirely different to what you were before you saw Denali, correct? The changes you’re ascribing seem to be ones of awareness, of consciousness. I’d say that heightened awareness brings forward consciousness of all things, not just human consciousness.

I respect the humility in your post, and I’m on the same page, as far as that goes. But I think it’s important to respect that we do bring a value to the world, just as bison and canyons do. Our existence does provide a benefit to the world – if it did not, I imagine we would not exist. That’s not to say, of course, that we can’t be destructive, and we certainly aren’t doing well collectively right now – but people do have something to offer the universe, just as does the butterfly, the wasp and the termite.

You asked: “Is it the mountain that is enriched by me making art of it, or is it myself and other beings that might appreciate it?”

Well, I don’t think it’s an either/or situation.; can’t the art bring benefit to you and other beings as well (I’ll include mountains as beings .. I think to not do so is unfair to mountains).

There’s a great book called “Do Glaciers Listen?”, by Julie Cruikshank. It’s focuses on the St. Elias mountain range area, and discusses at length some of the belief systems and relationships the Tlingkit and Athapaskan people of those regions had with the land (as well as various other native cultures through different parts of the world) – and they very deeply hold that the wolves, the glaciers and the mountains all have spirits, and those are in relationship with ourselves. I can’t imagine why they would not be.

Cheers

Carl

Hey great shot and great dialogue to go with it. Taku skan skan…spirit in everything, wind and waves, pine and palm.

Hey Mark,

What a cool phrase!

I have this one here on my Facebook Profile: “Forget not that the earth delights to feel your bare feet and the winds long to play with your hair.” — Khalil Gibran. Another favorite of mine that speaks to this quality is attributed to Tsleil-Waututh First Nation Chief Dan George, from what is now British Columbia: “If you talk to the animals they will talk with you and you will know each other. If you do not talk to them you will not know them and what you do not know, you will fear. What one fears, one destroys.”

Hope all’s well in the east.

Cheers

Carl

thanks!